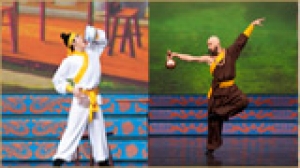

יאנג ג'י מוכר את חרבו

Outlaws of the Marsh is one of the four classics of Chinese literature. Set in the 12th century during the Northern Song Dynasty, the book narrates the adventures of 108 outlaw-heroes atop Mount Liang.

Written during the 14th century, this novel was inspired by folk tales about an outlaw band during the reign of Emperor Huizong. Amongst the bandit brethren are some of Chinese lore’s most colorful heroes: a drunk monk, a tiger fighter, and at number 17 of 108, “Blue-Faced Beast” Yang Zhi.

Yang Zhi was a descendant of the Yang clan, the famous family of warriors who defended the Middle Kingdom against foreign invaders (featured in Shen Yun’s dance Lady Mu Guiying Commands the Troops). Standing seven feet tall, Yang Zhi’s face sported a large blue birthmark and striking whiskers, beneath his trademark broad-brimmed hat.

Yang Zhi was a highly accomplished martial artist. He knew all 18 forms of armed combat, and wielded a spear with singular prowess. But his source of pride and joy was his saber—the fastest, sharpest blade south of the Great Wall.

No Ordinary Saber

The saber was a treasured family heirloom with three incredible features: it could cut through any metal without leaving the slightest indent on its blade; it could shred a strand of hair by simply blowing it against the blade; and it could kill a man without leaving a blood stain.

All signs suggested that Yang Zhi was a talented young man with a bright future. Unfortunately, he was also blessed with incredibly bad luck.

A shipment of imperial treasures under his charge capsized while crossing the Yellow River. Empty-handed, Yang Zhi returned to the capital hoping for clemency. Instead, he was discharged.

Another official contracted Yang Zhi to safeguard a delivery of precious gifts. It was a long, perilous march through remote, robber-infested territory. Yang disguised his caravan as common merchants and traveled only by day under the scorching sun. The precautions were to no avail. His exhausted laborers begged for a break from their heavy load. Resting in the shade of a few desolate trees, trouble found them.

No Ordinary Wine

A man, innocent-looking enough, approached carrying a huge wine vat. The parched laborers begged him to sell them some. Poisoning people by drugging wine was a popular trick back then, and naturally the hapless Yang Zhi hesitated. But when he saw his workers drinking with no ill effects, happily urging him to try some, he drank some too.

No sooner had he put down his bowl than he saw his men collapsing around him, one by one. Clutching his stomach and already wobbly, Yang Zhi knew he was tricked. As conmen crept out from the woods to simply pick up and take the precious goods, Yang Zhi could do nothing but flimsily brandish his sword at the spinning world around him, before he finally fell to the ground.

Upon waking, Yang Zhi’s men quickly abandoned him to avoid accountability. Rejected and penniless, Yang Zhi made his way into town.

An ancient Chinese axiom says: “A hero travels not without his sword.” But in the depths of despair, Yang Zhi was left with no choice but to sell his ancestral saber.

In the marketplace, an odious villain showed up to fan the flames. Yang Zhi, again finding himself at the heart of trouble, got some payback this time, and liberated the townsfolk of their loathsome oppressor.

Later, while roaming about, “Blue-Faced Beast” ran into the good-bad monk Lu Zhishen, and the two eventually found their way to the Mount Liang brotherhood.

The Shen Yun 2013 dance drama Yang Zhi Sells his Sword is based on chapters from Outlaws of the Marsh, and highlights the hero’s Robin Hood-ian qualities.

3. פברואר 2013