“Nature does not hurry, yet everything is accomplished” —Laozi

Have you ever dreamed of escaping urban life, at least temporarily, to a secluded mountain? A place where you can feel at one with nature. Where your heart can regain tranquility... Sounds nice, doesn’t it?

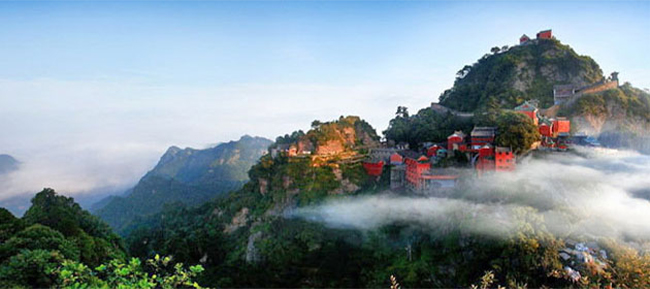

Well, some of the world’s most mystical, picturesque, cloud-shrouded, high-altitude mountains are found in China. At the ancient center of Taoism and tai chi is one such mountain range known as Wudang.

Located in central China’s Hubei’s province, the Wudang Mountains and their timeworn temples have long been home to those who devote their lives to the Tao, or the Way.

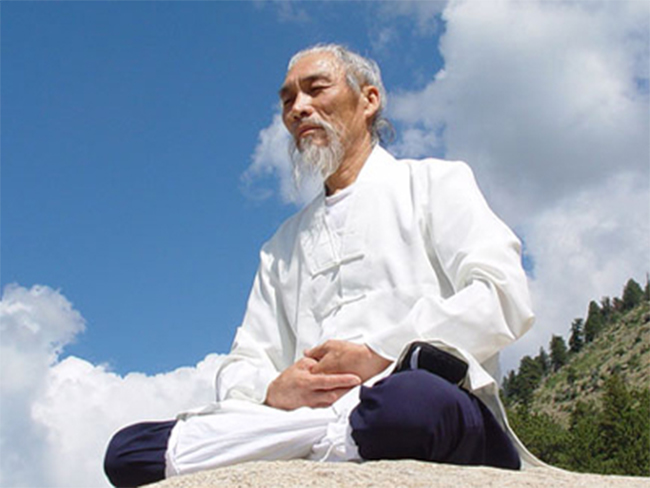

Tai Chi’s Immortal Founder

Once upon a time, well before throngs of avid pilgrims began trekking up endless stone staircases to Wudang’s magnificent peaks, lived a legendary man named Zhang Sanfeng.

Master Zhang was born in the twelfth century during the Southern Song Dynasty, and it is believed that he lived to be over 130 years old. Nobody knows when exactly he “disappeared,” but he is said to have achieved immortality in his lifetime.

According to the official work The History of Ming, Zhang was a towering 7-foot tall man with a noble posture. He wore the same Taoist robe year-round. He abandoned his secular life, wealth, property—even his worldly desires—and opted to live the life of a hermit. After wandering for some time, he finally settled down in the Wudang Mountains.

“This mountain will one day become very famous,” he declared.

Master Zhang was an unparalleled martial artist who was adept at Shaolin kung fu, the Chinese straight sword, and many other styles of martial arts.

And yet he also mastered the internal martial arts, and, most famously, is credited with founding the slow-moving tai chi spiritual discipline.

As legend has it, one night Master Zhang was visited in a dream by the Taoist deity the Jade Emperor. The Great Jade Emperor, the ruler of heaven, taught Master Zhang the secrets of the Tao. Upon waking, he was inspired to establish a martial arts practice based on internal energy, as opposed to physical strength; a martial art in which yielding overcomes aggression, and softness overpowers toughness.

And thus tai-ji-quan, or tai chi, was born.

Master Zhang’s tai chi was put to the test when he was attacked by a gang of bandits. No amount of punches or kicks could land on Master Zhang (If you’ve ever seen the movie Kung Fu Hustle, you may be familiar with how elusive a tai chi master can be.). As he kept evading his attackers, they eventually became exhausted, and he then struck them down with ease.

When the Emperor Writes

Although tai chi is mostly known today as a soft martial arts form that can improve your health, in reality the practice has strayed far from its original purpose over the centuries. What Master Zhang first founded was intended as a practice of self-cultivation, or spiritual elevation.

“What is essential to the practice of the Tao,” Master Zhang is quoted as saying, “is to get rid of cravings and vexations. If these afflictions are not removed, it is impossible to attain stability. It is like a fertile field. Until the weeds are cleared, it cannot produce good crops.”

“Cravings and ruminations are the weeds of the mind,” he said. “If you do not clear them away, concentration and wisdom do not develop.”

Being the sage that he was, many emperors sought him for advice on state and military affairs. But Master Zhang mostly proved hard to find.

Emperor Yongle, the Ming Dynasty’s third emperor, was lucky, however, and received a reply to his letter. Master Zhang knew that the emperor had everything except longevity, and so he responded by writing to the emperor that the key to longevity is to attain a peaceful heart by relinquishing worldly desires.

The emperor was so grateful for the advice that he declared Wudang a royal mountain, and ordered the construction of 9 palaces, 72 temples, and 36 nunneries on Mt. Wudang as a way to further promote the Tao.

This is why the Wudang temple structures seen today are reminiscent of fifteenth century Ming Dynasty architecture.

Master Zhang’s prediction proved true—Wudang became very famous.

The Old Sage

Some 2,500 years ago, at roughly the same time Buddha Shakyamuni taught on the Indian subcontinent, Laozi (Lao Tzu) and Confucius were teaching in China.

The Records of the Grand Historian tells of how Confucius sought the great Taoist Laozi to learn from him. The encounter left Confucius profoundly dumbstruck for three days. In other words, there was no “Confucius says” for three whole days.

When Confucius finally broke his silence, he said: “I know how a bird can fly. I know how a fish can swim. But I do not know how Laozi could rise and fly like a sublime dragon riding on clouds in the sky.”

Before Laozi departed China through the Western Gate never to be seen again, he left behind his teachings, written in 5,000 Chinese characters—a book now known as Tao Te Ching. Though Laozi is not recorded as having travelled to the Wudang Mountains, his Tao did.

Surviving the Cultural Revolution

Taoism played such a central role in traditional Chinese culture and thought that it became a target during Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution (1966–1976). The Chinese Communist Party’s materialistic, ultra-leftist ideology left no room for the Tao, the Way of the universe, or the law of nature.

Instead, the Party taught generations of Chinese to “struggle against heaven and earth,” to quote Mao. At the height of the Cultural Revolution, Mao’s Red Guards murdered Taoist monks and nuns, forced them to marry, and sent them to labor camps. They burned their sacred books and razed Taoist temples across China.

They also set out to destroy the historic temples of Wudang.

But greeting the Red Guards on the front steps of a temple was a 100-year-old Taoist nun, Li Chengyu. She had sealed her lips with glue before sitting on the temple’s steps to meditate without stop for several days as a form of non-violent protest.

The Red Guards were amazed by her determination and spared her. The temples in the area were saved, and several Taoists were allowed to remain.

Inner Peace

Whether you are seeking the Tao, searching for a quiet place to search for tranquility, or just looking for spectacular scenery, adding Wudang to your bucket list might be a good idea.

It is a deeply spiritual experience to walk among cloud-wrapped temples as curls of incense smoke waft through the air, colorful prayer flags flutter in the crisp mountain breeze, and formations of martial artists perform slow, fluid movements before a breathtaking mountain backdrop.

Shen Yun’s 2020 dance Taoist Destiny is set deep in the Wudang Mountains, where a Taoist master trains his disciples, and one warrior takes a leap of faith.