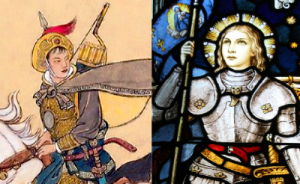

In this series we look at historical figures from China’s past who have intriguing Western parallels.

China has had its fair share of seemingly crazy monks and Taoists. Ji Gong is probably the most famous. In the West, the monk most notable for his peculiarities is Joseph of Cupertino. And the two have much in common.

Both Crazy Ji, a Buddhist monk who lived in the Southern Song Dynasty (960-1279), and Joseph, an Italian friar who lived in the 1600s, were said to have superpowers. Both had eccentric personalities. And both were abused and cast away before being ultimately revered.

Joseph of Cupertino

Known as “the flying friar,” Joseph was so pious he couldn’t stop levitating during Mass. But back then, rather than being a sign of a divine connection, levitation was often believed to be associated with witchcraft. He was ostracized and denounced by the Catholic Holy Inquisition.

His life story is beautifully captured in the 1962 movie The Reluctant Saint. Growing up, Joseph wasn’t the coolest kid on the block. He was awkward and a slow learner, had a poor memory and a short temper, and couldn’t manage to do anything right. His mother tried to get him apprenticed, but he dropped dishes as a dishwasher and failed as a shoemaker. When he finally found a place that would accept him, it was a Franciscan monastery.

Before he could begin his training for priesthood, though, Joseph had to start out doing servant work. Over time, he began changing for the better. He became gentle, humble, and kind. He even became more careful and successful in completing his tasks. Above all, he was exceptionally devoted to his faith.

Joseph soon began exhibiting miracles. In one well-known incident, he was so moved by Christmas carols being sung that, while he was kneeling, he began to levitate.

In all, over 70 instances of Joseph levitating have been recorded. As word spread about this incredible friar, people came to him to seek advice and confess their wrongdoings. And in turn, Joseph was able to help many people in his lifetime.

Ji Gong

Perhaps you’ve learned of Ji Gong from Shen Yun dances like Ji Gong Abducts the Bride, or Crazy Ji Saves the Day. You may recall him as a quirky character with ragged clothes, tattered shoes, and a broken fan.

In the strict Buddhist order of twelfth century China, Ji Gong was a nonconformist. With his meat eating and wine drinking—both taboos—he was kicked out of Lingyin Temple, and became an itinerant monk who relied on begging for food.

But Ji Gong had a strong sense of justice and, like Joseph, loved helping others and was deeply devoted, even if in an unusual way.

Ji Gong’s story is also beautifully captured (another parallel!) in the 1985 Chinese TV mini series by the same name (though really it’s the first six episodes worth watching and it tails off after that).

There are a number of legends about Ji Gong rewarding the good and punishing vice, healing the sick and helping the poor. Among the many miracles attributed to him, it is said that he could freeze evildoers (as in “don’t move,” not as in ice cream) in their steps simply by pointing his finger at them, and then release them at will.

In one popular story, Ji Gong was helping construct a temple in Hangzhou City. When they ran out of lumber, he began teleporting logs from a forest in Sichuan province, some 900 miles away. The massive logs just started shooting out of a well one by one, like some magical lumber portal.

All the other monks quickly piled the logs, while another monk was in charge of counting them. When they had what they needed, that monk yelled: “Enough!” But Ji Gong had already summoned another log. Hearing the monk, he stopped the log immediately, which remained half submerged in the well. Today, there is a pavilion built over this well, which was named the “Divine Teleportation Well.”

For more about Ji Gong, how he abducted a bride to save a village, and the flying peak boulder, see this article.

***

In spite of being continents apart, these two monastics seem to have been cut from the same robe. In their day, they were ridiculed as well as recognized for their compassion, depending on the perspective. In time, Joseph was canonized (1767) as a saint, and Ji Gong became revered as a deity.

Betty Wang

Contributing writer