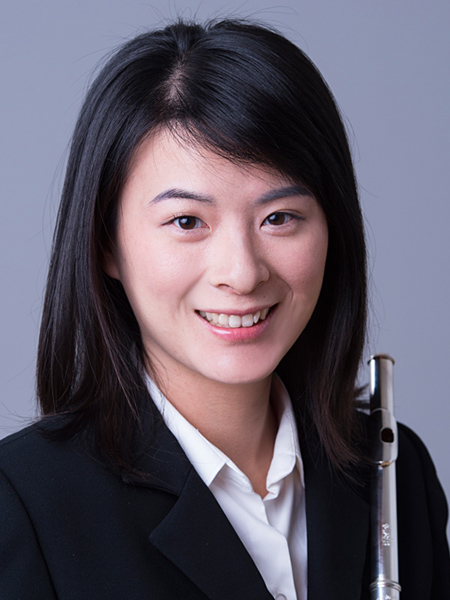

Music is the sun around which Chia-jung Lee’s world revolves. But her skies weren’t always clear. In graduate school, the altruistic flutist found herself heading into a fog. Questions like: “Why did I choose music?” “How can I use these skills to help others?” and “Where is all this going?” plagued her daily. But soon, a stroke of fate helped Lee define her music with newfound purpose.

Q: How did you begin as a musician?

CL: When I was 8 years old growing up in Taiwan, my parents had me learn piano to curb my hyperactivity. Three years later, I saw Taiwan’s “Flute Princess” Ellie Lai playing a Disney theme song on TV. I thought the music was just wonderful, and decided to take up the flute.

I dreamed of becoming a world-class performer, and one step at a time I was achieving all my goals. But when I came to Boston for my master’s, the world suddenly seemed a whole lot bigger. I realized I still had so much to learn.

I began reevaluating my path as a musician and my life goals. I kept asking myself why I chose to major in music. I thought back to the TV show that first inspired me to study flute, and music’s power to influence people. I wished my music could help others forget their worries, if only for a bit.

Q: What were your career plans?

CL: The last year of grad school was the most perplexing year of my life. Everyone around me was happy and eager to graduate, whereas I remember crying a lot because I didn’t know what to do next. It wouldn’t have been hard for me to find a job, but I was bothered by thinking about what music really meant to me, and even the meaning of life. Though I felt really lost, I still had the sense that music was meant to help others. Except I didn’t know how I could help. I had no plans.

I thought I might find a job teaching, and that would allow me to help others and be happy. Although I didn’t know what the future held for me, I knew I didn’t want to use music just to prove my own abilities.

Q: How did you first come across Shen Yun?

CL: After grad school, a friend forwarded me a Shen Yun recruitment letter and a link to the website. When I read their mission statement—using classical Chinese dance and music to revive traditional Chinese culture—my eyes sparked. “YES!” I thought, “This is it!” The part about reviving culture really excited me. It seemed like something very meaningful that could benefit the world. I then watched many of the artists’ video profiles online, and I was very moved by how sincere they were.

Q: So you decided to audition.

CL: I did. And during my audition I was given a Shen Yun composition to sight-read. I’d never played Chinese music before, but it somehow seemed familiar. I thought the melodies were beautiful. We made an immediate connection.

Maybe it’s because of my background. I studied classical Western music most of my life, but when it comes down to it, I’m still not a Westerner. It’s not my culture. It’s not in my bones. When I first heard Shen Yun’s blending of Chinese and Western instruments, I realized this is what really resonated with me. I felt this sense of freedom of finally understanding what all my years of study and practice were for.

Q: When was the first time you saw a Shen Yun performance?

CL: Actually, it was the very night of my audition. It was at Lincoln Center, and I cried several times. At the sound of the gong being struck to open the show, the energy jolted me awake and my tears came streaming down. That was the first time I was touched like that by a performance.

After the show, I said to a friend sitting beside me: I am so proud that our culture is this beautiful, that it’s being widely promoted in Western society, and so professionally.

I’d only just auditioned and didn’t know whether I’d been accepted or not. But as I watched the performance, I felt full of anticipation¬— joining Shen Yun would be my greatest honor.

When it came time for the curtain call, I found myself crying again. The dancers came back on stage to say goodbye, and the musicians in the pit stood to wave at us. I remember sitting in the audience but wishing I were in the orchestra pit, waving to the audience and saying, “Goodbye, hope to see you next year!”

Q: That was 2012 when you joined Shen Yun. And only a few months later, the company debuted its Symphony Orchestra at Carnegie Hall.

CL: That was my first time performing at Carnegie Hall. I remember thinking: “Wow, this day actually came; and so soon.”

That was also Shen Yun Symphony Orchestra’s first-ever concert. The night before the concert, we were very excited and a bit nervous, to be honest. We knew we were going to be a part of something historic. I think everyone really cherished the opportunity, and we were perfectly together in spirit.

During the show I felt something magical. There was one place where I don’t play for eight measures. I sat there calmly with my eyes closed, and surprisingly, it felt as though the music was flowing by itself. As if it wasn’t us playing at all, but gods helping us. Many musicians felt the same. It was the first time I experienced that—none of our rehearsals had reached that kind of state, that ambiance.

Q: You’ve now been with Shen Yun for two years. Is being part of this orchestra what you had expected?

CL: Tell you what, during performances, when the entire orchestra enters this state of being very focused, I feel this immense energy. It’s a kind of energy that far exceeds the brief entertainment that my music on its own used to bring people. It definitely feels like something so much greater than just me.

I’ve experienced how, if you put your heart into your playing, the audience feels it at once. In my two short years here, I’ve felt myself elevating as an artist. I’ve found the true purpose of music, and life. I’m enjoying the process of constantly climbing to the next level. It’s a never-ending journey, and a joyful one, too.

* * *

Shen Yun Symphony Orchestra is now on its third concert tour. Chiajung Lee and Shen Yun return to Carnegie Hall October 11, followed by five other cities.

Read Chia-jung Lee’s bio

More about Shen Yun Symphony Orchestra and its upcoming performances